No Sugar-Coating It: While Trends are Promising, Kids Are Still Slurping Too Many Calories

By Keith-Thomas Ayoob, EdD, RD, FADA

Associate Clinical Professor, Pediatrics (Child Development); Director, Nutrition Clinic, Children’s Evaluation and Rehabilitation Center; Albert Einstein College of Medicine, Yeshiva University

That’s the word from the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) in its latest report on beverage consumption among teenagers during the years 2007-2015 (Miller, 2017). The CDC does this annually but this report looks at the changes over time and things seem to be improving…somewhat.

The teens surveyed were all in grades nine – 12 and they were simply asked whether they drank soda during the past seven days, and how often (daily, every one to three times in the past week, etc.). The improvement is pleasantly surprising. More than one in three teens used to drink soda daily in 2007. Now only one in five do.

education, elementary school, drinks, children and people concept – group of school kids with soda cans talking in corridor

education, elementary school, drinks, children and people concept – group of school kids with soda cans talking in corridor

It’s not all rosy

Fewer kids are also drinking milk and 100% juice. Daily milk and juice consumption each dropped by seven percent and this drop occurred almost entirely during the latest four years of the study.

As for other sugar-sweetened beverages, like fruit-flavored drinks, powdered mixes, sweetened coffee drinks, bottled iced tea, etc., the survey didn’t even ask about them. Questions about water and sports drink consumption were added to the survey in 2015, so data on these will be available eventually, but there are no plans to even ask about those other beverages teens (and other kids and adults) drink.

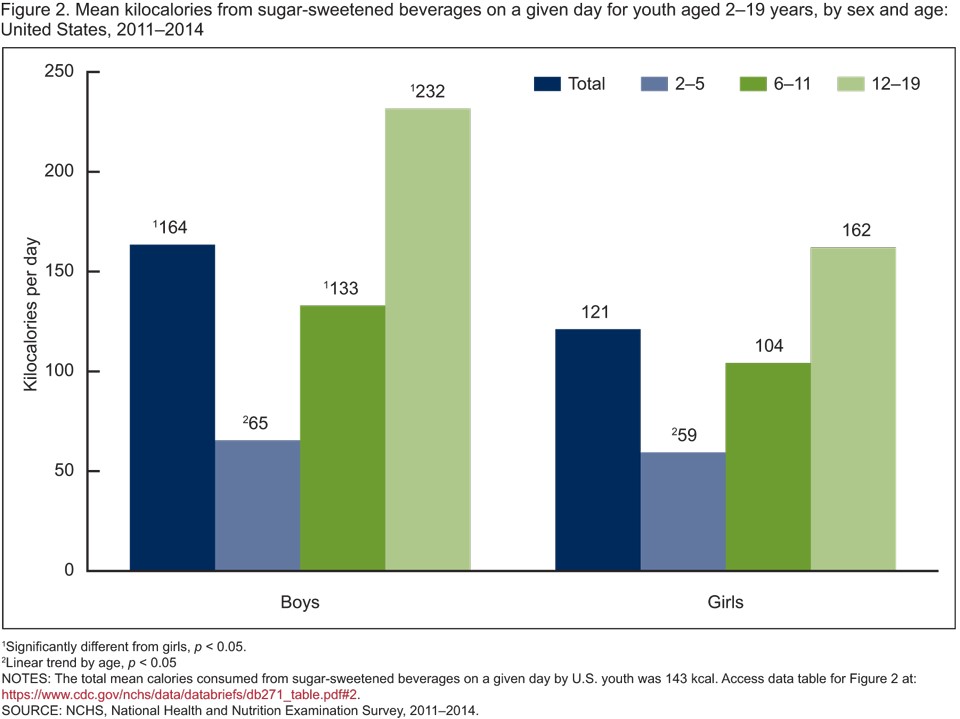

That doesn’t mean that consumption of those omitted beverages isn’t being tracked elsewhere by the CDC. Indeed, the CDC’s latest Data Brief, issued in January 2017, asks about all sugar-sweetened beverages, not just soda (Rosinger, 2017). This report tells us that approximately two out of three children drink at least one sugar-sweetened beverage per day. These empty-calorie drinks provide boys with 164 calories and girls with 121 calories. Here’s the calorie breakdown by age group and gender:

As for juice, in my 30+ years as a clinician, I’ve taken thousands of dietary histories. I can tell you that many non-juice drinks are called “juice”, especially in lower income families. If it looks and tastes like juice or is marketed as “having 5% real fruit juice” then they may consider it to be juice. I’m not sure why, but for some reason, not having bubbles in a fruit-flavored drink allows it to be perceived as “juice.”

Despite the reported decline in soda intake, 47% of sugar intake by everyone over age two years came through beverages, according to the most recent analysis provided to the 2015 US Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee (DGAC, 2015). This, and the CDC’s Data Brief tell us that there’s a lot of room for improvement, in terms of reducing empty calories from beverages. Can you imagine if even half of that sugar intake could be reduced, just by swapping those empty sugar calories for a beverage with a sugar substitute like stevia?

Drinks containing sugar substitutes deserve closer attention for their ability to help comfortably reduce the consumption of sugar-sweetened drinks without leaving people feeling deprived. There is still a stigma about this and it is scientifically unfounded. We want children (and people of all ages) to drink plenty of water and calorie-free beverages. But water isn’t useful until people drink it. Enhancing the flavor with a natural sweetener like stevia can help motivate people – especially children — to drink more water. A few things to remember about stevia:

- The science on the safety of stevia in beverages and all foods for children (and all age groups) is well established and scientifically sound. I’d never recommend it to my patients otherwise.

- Children already DO drink beverages with sugar substitutes. To what extent? We don’t know, nor does the CDC, because they simply do not ask this question. This is a missed opportunity.

Reality check

I’ve always positioned calorie-free beverages as a “water alternative” for children and anyone wanting or needing to drink more water but without getting extra calories in the process. Indeed, drinks that get all their calories from sugar are a waste of calories for anyone at any age. It’s simple: if people like the taste of their water, they’ll drink it more willingly and easily. Moreover, calorie-free beverages with sugar substitutes like stevia are arguably a better choice for children than empty-calorie sugary beverages.

REFERENCES

- Miller G, et al., (2017). Trends in Beverage Consumption Among High School Students — United States, 2007–2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2017;66:112–116. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6604a5.

- Rosinger A, et al., (2017). Sugar-sweetened beverage consumption among U.S. youth, 2011–2014. NCHS data brief, no 271. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics.

- US Department of Health and Human Services and US Department of Agriculture. 2015–2020 Dietary Guidelines for Americans. 8th Edition. December 2015. Available at http://health.gov/dietaryguidelines/2015/guidelines/.